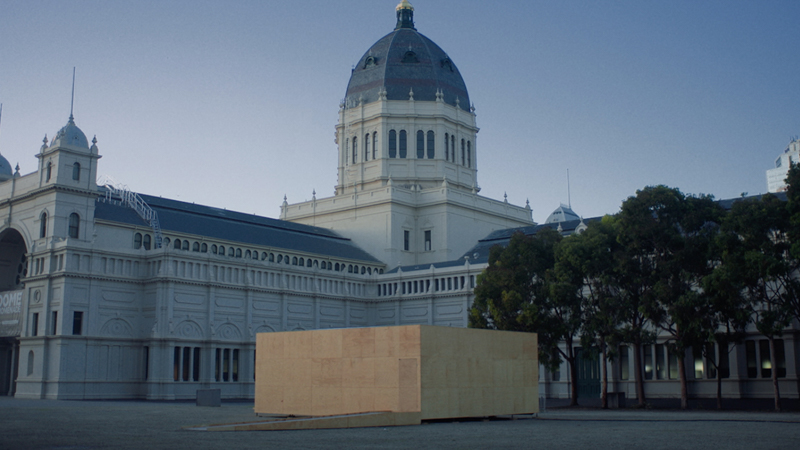

Resonance follows the Artamidae Quartet preparing for a performance in the ANAM Quartethaus, a small wooden box outside the Melbourne Exhibition Centre. The space was designed for a listener to experience the visceral and intimate experience of a string quartet playing, a unique event lovingly captured by co-directors Kate Vinen and Jayden Rathsam Hüa.

How did resonance first begin?

KATE VINEN: Jayden and I did a pitch for a competition called Music and Place, run by the Australian Film Television and Radio School (AFTRS) and the Australian National Academy of Music (ANAM). We had worked together on a previous project we won through a pitch called The Caretakers a few years earlier.

So it began with the pitch, finding out we were successful, and beginning the process of planning a trip to London to follow the Artamidae Quartet to what was going to be the first pop up in history outside the Royal Albert Hall in London. However, due to a combination of COVID, Brexit, the war in the Ukraine, the Quartet got to the port in London, and couldn’t get through. The ship got turned around and went back to Singapore, and eventually back to Melbourne, where we ended up filming a couple of years later.

Wow, I didn’t know that it had taken a couple of years…

JAYDEN RATHSAM HÜA: I believe back in 2021 we started.

How’s it been finally getting that out into the world?

JRH: Weird. It kind of enters a limbo when things beyond your control are affecting the timeline. It’s different to a project that would have taken so long, but you’re constantly working on it. And at times, it felt that way. But there were big month-long gaps where we were just waiting on word from another department, whether it be ANAM or AFTRS, based on some kind of clearance or something. So the project very much felt like a background task that was running. And then suddenly it would be at the forefront. And then it would recede and then come to the forefront. I just got used to Resonance as a project that was cycling away in the background.

KV: Yeah, I think it’s taught me, one, make sure you love your collaborators. Jayden and I would never have thought it would take so long. But I really love Jayden as a friend and as a collaborator. And two, it taught me you have to become a professional filmmaker, it’s like this is one of your projects on the burner. And when it goes from a back burner to a front burner, no matter how busy you are with other stuff, you have to be available for it.

So it does feel satisfying to have had it premiere at the Sydney Film Festival. Documentary truly is a wild thing. Every documentary is a miracle because they so often fall over.

JRH: Something that we’re very grateful for is the fact that it was paired with a live performance String Quartet that was organised. It’s a rare opportunity to have the screening bundled up with another exciting, embodied experience that feels spiritually connected with the messaging. It added another layer of meaning to the film and the screening. It was a cool, immersive experience for me as well, because the music performances were new to me too. It was nice to see a screening presented in a different form like that. Yeah.

I was actually going to ask about the screening because I love to see the combination of film and music, what was the event like?

KV: Something about it felt healing to me, because I grew up in a very musical family. My aunt spent her whole life in the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, so as a child, I would often be in Melbourne, at the ABC Art Center during their rehearsal, watching them practice. I played clarinet and piano, and I was in the school band and did singing, blah, blah, blah. I had a lot of pressure to be a musician and my mother’s always mourned that I didn’t continue with that, they still have my dusty clarinet in a box somewhere in their house.

I feel like it proved something to me where it’s about being a creative. Yes, I could be a musician right now. I could be a dancer. I could be a novelist, but I’m drawn to film. So it felt really healing for me on a personal level.

It was a lovely event! I personally think there’s few things better than live music. And we live in a world of screens and disconnection and distraction and to be in a space where everyone’s attention is focused. You’re forced to be quiet. I just felt like it created this beautiful sacred space, which is very relaxing, I could feel its magic working on me. So it added this extra layer to the screening, which I thought was really great.

That’s so beautiful. You touched a little bit on your very personal connection to music and to the film, Jayden did you have a connection like that as well?

JRH: Yeah, cello was a massive part of my life. I played cello for over 13 years, throughout my childhood. I majored in performance for my HSC so my whole schedule was centered around classical music. Spending some time away from it has given me an interesting little moment to breathe. Because for the longest time, classical music felt like work, it felt like a chore. It was super technical, and the reason I was doing it was less about the enjoyment of the music and more about whether it could get me high HSC marks, really it was a form of study. So it was difficult for me to find the organic sense of joy and artistry in what I was doing, I was robotic.

Having spent some time away from that, and having this opportunity to do something in the film world about classical music, it invited me to look at it from a different perspective. Especially with the Quartetthaus, and the philosophy that underpins why it was constructed, which is to shine a light on the intimacy shared not only between the performers, but also with the audience. It refocused my understanding of classical music in a far more beneficial way and I was able to fill the shoes of the audience. I was able to enjoy the music for the reasons it was written rather than use it as a mechanism to achieve something on an academic level. So yes, making the film had a very strong connection with my childhood but it also recontextualized it in a pretty cathartic way.

I like how you mentioned the intimacy of the Quartetthaus that was constructed in Melbourne outside the exhibition center. It’s so pared back and minimalist and it looks so small. What was it like filming and in this really tight space?

KV: Well, I feel like it’s a part of being a filmmaker, we want to get better at it so that we can assess the situation and go, Okay, this is what needs to happen. It was a conversation between Jayden, Petra Leslie, the cinematographer, and I, about how we work around certain things. So everyone you see, that audience was specifically there for us to film. We had them for a period of time. So I feel like the time we had was probably the biggest challenge, working quite quickly.

JRH: I think on top of time, it’s tricky because they’re playing the performance continuously and you have the audience listening to the piece. As we mentioned on the panel, it’s not about capturing the moment exactly as it happened, but rather understanding the spirit of the event, the spirit of the moment, and getting what we need to emulate that in the edit. So knowing when there are significant moments during the performance, and finding the right members of the audience that best represent the feeling of reflectiveness and intimacy and emotion and having that reflected in their faces, I think is something that we really strove to do.

The challenge is folding moments from different times and spaces within the box into something that feels coherent, spontaneous and organic. It was a very interesting exercise to remove ourselves from the way things happened on the day when it came to the edit suite, and more so recall the feeling of it, and piece together the most authentic representation of that.

I felt like I was carried along with that journey. The film is about construction, of course you begin with the physical space being constructed and then the rehearsal room is part of constructing the performance. Could you speak to that?

KV: I know from previous conversations that Jayden and I have had, we are drawn to process and how things are made. There’s something beautiful and human about it. It’s what we do. We build things, we create things. Give a human being a piece of land and they make a garden, we’re just creators. Our story fell through when we lost going to London, we were going to follow the musicians over there. And I think when you add planes and travel, you have instant excitement. So we needed to look at what we had; we had the construction of this box, we had the box itself, and we had the performance. So it also comes down to how you can tell a story. So the construction adds to that, what is being made and why and there’s something I love that’s quite surreal about it. Like, why create this thing? Oh, because the humans like to listen to music in an intimate space together.

And it’s funny, because there’s a shot at the beginning when the box is finished, and then you see this giant building behind it, and it’s just so dwarfed. It’s so small. I love that.

KV: You’re right. It’s the visual juxtaposition for me, I love that the building behind is old and ornate, and then it’s this minimalist, simple thing. I love that it doesn’t distract from the beauty of the music, the music is that you go for.

JRH: I see the opposite of what you would expect from the design sensibility of a concert hall, right? A concert hall is so grand. It’s so ornate. So classical in design. It’s also theatrical and dramatic, all the paintings and the architectural embellishments and the lavish seats. It’s so vacuous in its scope. And you look at the Quartetthaus, and it’s like a shoebox.

I think classical music can be viewed as less intimate, more technical and sterile. There’s that sense of distance between the audience and the music, but more so than that, you have this sense of anonymity. You go to a pop concert, you go to any other kind of musical performance and the personality of the musician is at the forefront. But you go to classical music, and everyone’s wearing black, and their demeanor is always the same. They’re very placid, very stoic, and they just play the music, they will emote, but it’s not the focus. And a lot of people that are listening to classical music, their eyes will be closed, they’ll let the music wash over them, and the person behind the music will disappear. And I think that’s flipped on its head in the Quartetthaus, the people behind the music are at the forefront. And the humanity of the performance is put front and center. It’s unavoidable. It is rotating on a stage 30 centimeters away from the front row.

KV: I love that there’s nowhere to hide. And it reminds me that sometimes we try and make intimacy this beautiful, romantic, perfect thing, but it’s also real and raw and wild.

For a lot of these types of classical musicians, it’s almost like their bodies become vehicles for the music. And in some ways, as directors, we also become vehicles for our films, did you find that you related to the musicians in your craft?

KV: Definitely, I relate to anyone creative. There’s something kind of weird about you where you want a stranger to have an experience. I’ll never understand why I will often put myself in challenging circumstances so that someone I don’t know will be moved or have an epiphany. That’s something we really have in common is that desire to create an experience, and it’s to deal with feelings.

JRH: And collaboration, I think that was one of the main things that I related to is that when you look at art, and you look at work and the way that it’s constructed, you think about the maker, and you think about the result, the product. But the funny thing is, not only does it relate to filmmaking, it relates to any industry, your workplace is defined by the personalities that you’re surrounded by. And the creation of art, when it’s a collaborative practice, is very much the same. The directors and the crew that make a film put their fingerprints into the final result.

The same can be said about a quartet. It’s the same sheet music, that’s not going to change, but not only are other people going to change the way that the music plays, but the relationship that’s shared between those people is going to change the way that the music is played.

If you had a favorite moment, or maybe an unexpected experience whilst making this, I’d love to hear about it.

KV: Jayden and I decided to co-direct and co-produce. I think it was unexpected. We knew we were good at communicating, but I didn’t know exactly how that would go. I found it quite natural in terms of who stepped in when, and it just made logical sense.

JRH: I think some of my favorite moments was the downtime between shooting, and it was just so nice to meet and chill out with the quartet members. There’s a valuable lesson to be learnt there, because everything that happens in a shot is a result of everything that happens around the shot. When they’re presenting in the interviews, all of that was coloured by the rapport they had with the crew and the conversations that flanked the interviews.

by Parker C. Constantine

Resonance

Sydney Film Festival